Here’s a case of two recent residential infill projects that neatly demonstrates several flaws in the way we think about plan for new middle scale buildings.

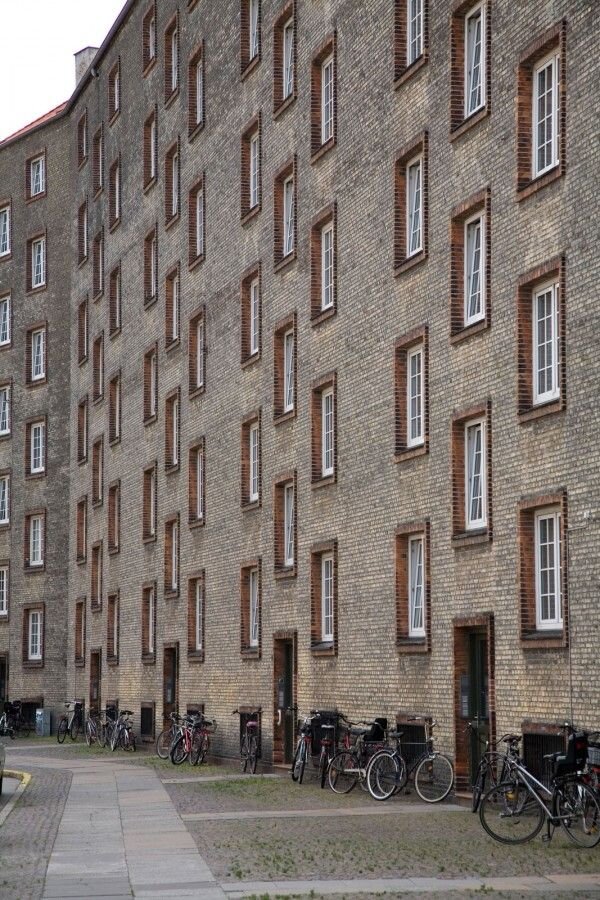

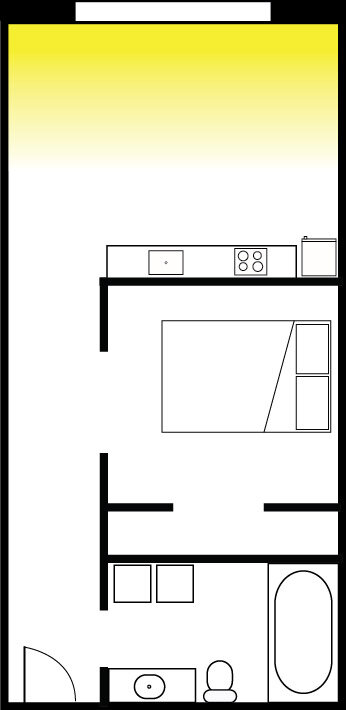

Case 1 is located about 100’ east of MLK Jr. Blvd. On paper, this building is doing what middle scale zoning should – providing a step-down transition between the midrise apartment zone (which happens to contain a brand new 5 story apartment building in this case) and the single family homes to the east. To be honest, it’s not even failing at that task per se. We like this building for a number of reasons. Its vernacular profile and consistent and calm architecture is timeless and skillfully executed. It presents a symmetrical, legible front to the street, and does not go through odd contortions to accommodate garages. It comprises five identical row houses in a line perpendicular to the street. The only complaint here is that this bread loaf loads its slices from doors facing the long side, which is an interior lot line. We’ll have more to say on this in a bit…

Our other case, located about 500 feet east, is on a corner site, with the outer side lot line facing Irving park. There’s not much positive to say about the architecture here.

This mess of arbitrary shapes and pointless rectangles is configured as a side-by-side. The building itself is extremely awkward. It’s three stories tower over its bungalow neighbors, due to the fact that its ground level is dominated by garages. This is one of those buildings were parking dominates and living space is shoehorned in around it. The two units suffer from the “floor is lava” problem, where the main living space is far enough from the yard that they have minimal connection to it. Unsurprisingly, the yard is just a patch of beauty bark surrounded by a 6’ “privacy fence,” Interspersed with posts that support stairs and decks for the levitating house above.

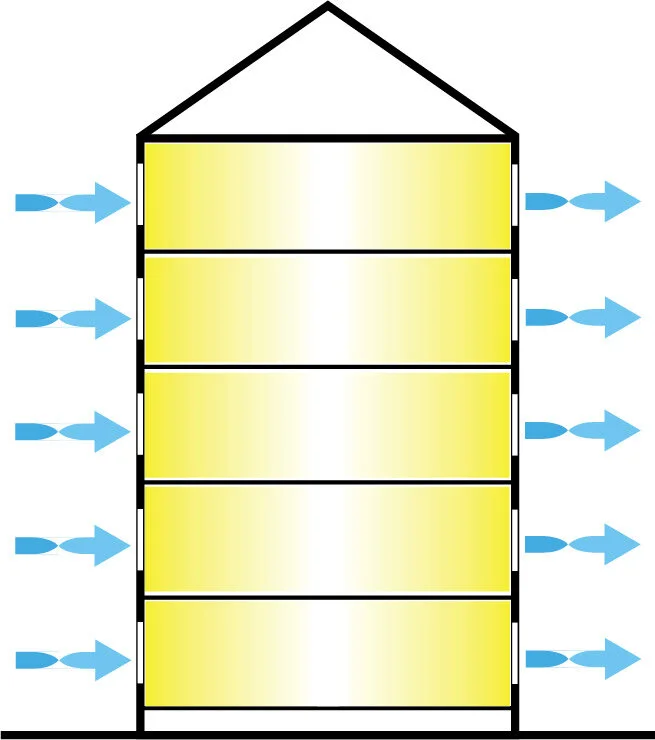

The gist of this post is that zoning orthodoxy instructs planners to put the “most intensive uses” along arterial streets, where there is high traffic (car and foot) and frequent transit. So far so good. The logic fails when we look at what this really produces. Broad brush zoning application doesn’t take things like Irving Park into account. Nor does it do much to relate bulk and height to the supposed intensity of a use, which, in residential areas, is simply measured in terms of number of units.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to have the taller of these two buildings between homes and mid-rise apartment blocks? Wouldn’t it make more sense for the side entry building to be on a lot where those entries can face the street, or better yet, a street with a big park on the other side? There’s precedent for the latter only a couple blocks away! Here’s a bungalow-bar type fourplex facing Irving park, with its entries facing the long side of its corner lot. How hard is this to figure out? The precedent is right fucking there, 200 feet away!

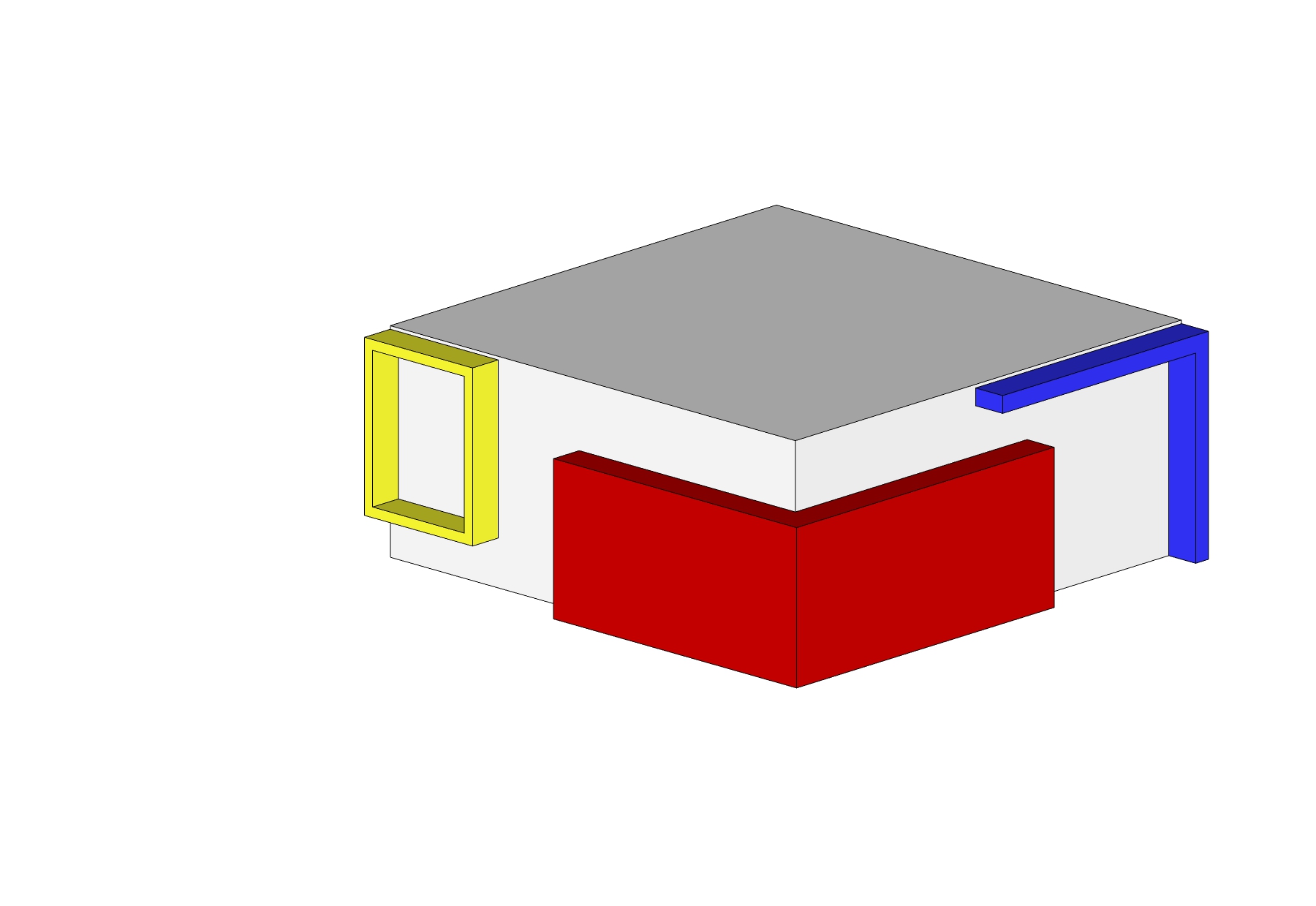

The big idea behind form-based codes is that the form factor of the building is more important than the internal configuration, since that determines compatibility.

This nice row of front doors seems kind of wasted here. Wouldn’t it be better to have these lined up facing Irving Park across NE 7th? Compare: