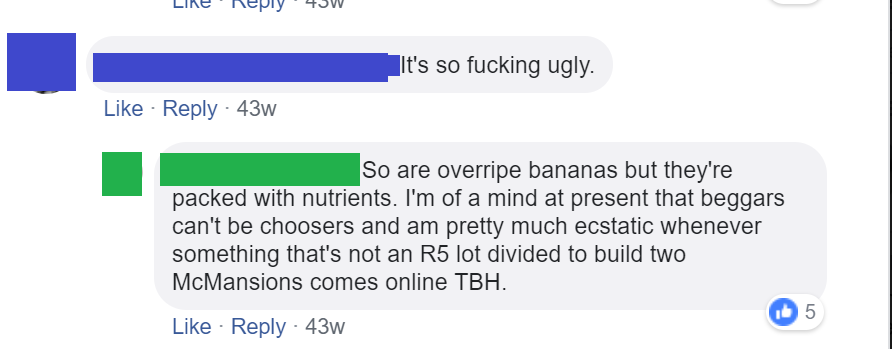

Recently, I have seen conversations in our community pitting the ideas of affordability, availability and design against one another in terms of new construction in Portland. A recent example, was an exchange over social media I witnessed between two friends of mine on the topic of a newly built apartment building here in Portland.

conversation in reference to building above.

We find ourselves at an interesting crossroads in Portland; we are experiencing record population growth and will continue to do so for decades to come. As a constantly growing region, it is important that we ensure that our fellow community members actually have enough physical places to live. Statewide land use law in fact requires all cities and regions plan for a 20 year land supply for housing, commercial and industrial. Housing availability, not just affordability, is one of my personal pet issues for our region. The way we currently have our city laid out zoning-wise in terms of its overall population capacity, we are simply not footing the bill for our own future growth. As someone who plans on being around to witness the next few decades of Portland’s story, I am afraid we are not rising to the challenges that are facing our community. We absolutely need more high-density infill in Portland to ensure there is enough housing available for the future citizens of Portland.

Are you ready for 50+ more years of Portland life with the Linden?!?!?!? 😢

NE12th/Burnside/Sandy

While I am concerned about us meeting the demands of our own population growth over the next couple of decades, I am also concerned about what the qualitative experience of living in Portland will be like decades from now. We do have a strong likelihood of having to accommodate millions more people in our region in the coming decades, due to factors like climate change. When we build new things in our city, especially larger pieces of construction like apartment buildings, we need to understand that these are things that can stay with us for 50 to 100 years.

Truly inspiring, I can’t wait to age in place here… Seattle time! 🤢

Seattleite Millennials/GenZ will be clamoring to preserve this wonderful piece of human history in 2060 - or not…

“We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

Buildings don’t just stand alone, they get to be a part of our everyday lives, the things we see and pass by on our commutes, where we hang out after work, or plain simply where we live. What we build now becomes the pixels in the background picture of our everyday lives. It may seem that we have entered a reality in our region where these two needs are now at odds; the need for more housing, and the need for aesthetically pleasing architecture for our community to be surrounded by as well as well-thought out spaces for people to occupy and build their lives around for decades to come.

Whenever I see this argument pitting design against housing, I can’t help but think:

Why can’t we have both?

Expanding housing supply is a “good.” Preserving historic architecture is a “good.” Planning places that encourage beauty, walkability, sustainability and sociability is a “good.” We believe it is shortsighted and foolish to pit goods against one another.

Look at this brand new beauty in McMinville (Hotel)

At P-D-X we have been chewing over the question of what “good design” is, and over the implications that come to mind for most people when they hear others talk about “good design” in architecture. We often hear that asking for better design is “Elitist” or adds “unnecessary costs” to projects that provide a functional use for our community - something we see in public housing all the time. I would personally like to challenge this thought process, and it is something that we do on a regular basis here at P-D-X Blog. It’s time to knock a huge hole in the false dichotomy of affordable vs well designed. Good design does not have to be expensive, it does not have to mean adding on additional costs to new housing, and frankly the conversation does not need to have an air of elitism tinged to it at all.

Part of the Goat Blocks off SE Belmont

This is a nice little pixel on SE Belmont, is asking for design like this elitist?

These are both new 3 story buildings, by looking at the amount of materials used, Can you guess which build cost more per sqft? Which one is better designed?

Most of the time, the best designed buildings aren’t the ones that you see on the cover of an architecture magazine or text book. They aren’t the buildings that architects and enthusiasts want to rave about around the world. They are the buildings that understand their role as a pixel in the background image of our lives, ones that simply choose to blend into the background, becoming a normal part of the city’s fabric, those are the buildings that represent good design. Those building examples, are often not the most expensive pieces of construction either.

In the past Jonathan has identified and broken down some of the elements that we regularly see in new construction around Portland that contribute to those new buildings often being seen as “ugly”. Simple design is often good design, focusing on tried and true elements is often good design.

Urban Design, as a discipline, takes a more holistic view of cities and districts and focuses on how the parts of a community add up to a greater whole.

When we talk about design, we’re also talking about things like curb cuts, curb radii, street trees, stoops, front porches, front doors, driveways, “eyes on the street,” etc. Some of these things are site design and arrangement elements, others take place in the public realm, i.e., the right-of-way, which we own collectively.

Bad Design

Some of the worst design we see in modern construction doesn’t come from low-budget efforts, but from higher-cost luxury designs. If anything, the wealthy happily prove time and time again that they are more than willing to lay down huge amounts cash for the most tasteless poorly designed housing imaginable, in fact, there is a whole other blog dedicated to just this point.

Images courtesy of Mcmansionhell.com

Portland does deserve high design but let’s be honest, if you don’t really have the chops in design skill and are more than willing to lay down the extra capital on higher quality materials and design, then don’t even bother. High design is great left for institutional developments and other organizations with higher capital and the grit to throw down in a type III design review.

If your goal at the end of the day as a developer or architect is to throw up a regular commercial/residential building in the city and collect a paycheck, then stop trying to cheaply pursue high design that looks terrible and just go with a tried and true simple, classic, and already affordable design pattern. Most of the time we need our new buildings to be a pixel in the image, a part of the scene, not the stand out kid in the class. We need architects to stop looking at every new piece of construction as a standalone piece of art formed by their own mighty hands, but as a player in the greater symphony of its location.

Somebody put Chad Kroeger from Nickelback in this symphony.

nice

In part because of our trailblazing architectural history, we can often find our best urban future in our urban past - no need to reinvent the wheel everytime we build something new.

Check out these neotraditional new construction examples by R John Anderson from the Small Developers Facebook group.

Believe it or not, the absence of extra materials for weird flanges, hats, and other pieces makes these buildings cost less to build.

We need more housing, we will need a lot more housing to keep up with future demand. But we have to remember that we aren’t just building housing, we are building places for people to live and build their lives. Places where people tell their own stories. Are we building the best setting for the story of future Portlanders? When we are building Portland, we need to be considering the perspective of future Portlanders.

Will we enjoy living there?

Will we still want to live in it or use it 50 years from now?

Will we be proud of it?

Everything in housing is a trade off, but we don’t have to trade off good design for affordability and availability. We have to change the way we interact with design at the regulatory level. The market will follow the path of least resistance around the codes and regulations we put in place, so we need to understand how the design rules we make play out on the drawing board when market actors are balancing regulation, design, and financial considerations.

We can streamline our design standards so doing the simple, time-tested approach to design is the path of least resistance. There is a common myth that better design requires more man-hours put into design. This implies that buildings basically design themselves and the default outcome is an ill-formed ugly building. Throw more hours at it, so the myth goes, and the design gets better, but the architect’s bill gets bigger. First, architecture is not a big enough share of total project cost to have a huge impact. Systems Development Charges (SDCs) for example, have a much greater impact on a developer’s pro forma. Moreover, much of our worst “developer modernism” reflects a pointless quest for novelty that is inherently wasteful. Slashing the architect’s fee to a bare minimum won’t have any discernible impact on rents either. For one thing, owners set rents to what the market will bear, and any savings in cost to to the investors. The overall design fee is trivial compared to land, construction, fees and labor costs.

Aura Burnside

Modularization and creating form based design codes so that it is less resource intensive for builders and designers to create reliable and abundant housing consistent with the design standards of the community is the key.

“Where design gets expensive is when bad design gets caught by design review and sent back to the drawing board for a do-over. It’s really the time and redundancy of multiple attempts where costs pile up. The bland and forgettable Aura Burnside was rejected multiple times before approval. It’s only as good as it is because the previous attempts were so bad. Developers wanting a quick one-and-done design review process could opt for a more traditional composition mode for a guaranteed outcome. This leaves discretionary review to those who a) have the chops for it, and b) count on high design having a real pay-off in terms of project value and feel like it’s a worthwhile investment. Communities have already done much of the hard work to figure out and codify a baseline standard for design of good fabric buildings.”

-Jonathan Konkol on Aura Burnside

In the past, we have proposed a transect type system, tools such as pattern books: simple, pre-approved designs that get to skip review because that have already been vetted are things that should be offered by neighborhoods to alleviate much of the friction in design review.

This isn’t a zero sum game; we can have both things, and we have every right to demand them. We can build the housing capacity we need while also ensuring that the environments we build will be enjoyed for generations to come. Someday Oregon’s population will be double what it is today, what is the best possible version of life in an Oregon with that many people? How do we start laying the groundwork for it today? We start by involving communities in planning for their future. Once we establish that we are going to grow, we must work for a grass-roots, community-supported vision of how we’ll grow. Already, pioneering groups are leading the way in this process here in Portland. We should expand and build on work like this.

All design is expensive. Good, bad, no new building is cheap, and no brand new apartment is going to rent for below market rate, unless it’s being subsidized.

Even adjusting for inflation, all the inputs to building, land, materials and labor, are more expensive than they’ve ever been. Loans aren’t cheap either. Therefore, no building is going to be cheap. Good design, bad design, it’s all expensive. Rolling over the good design argument in favor of availability and affordability does not compute when it is taken into consideration with the daunting other costs associated with new construction.

Let’s take just one minute to get together and talk about design as a community, talk about what we want to do and see in our home for the following decades of our lives. Let’s wrap that up into a nice package so that builders have an easy path and know exactly what they need to do when it comes to building Portland. No more need to have every new piece of construction caught up in months of debate over design with the community, the community should set their expectations ahead of time.

We as a community need to get together as a group and have an honest conversation about what our growth over the following decades is going to look like. We will need to add more housing in all neighborhoods, let’s plan that out ahead of time so nobody is taken by surprise. Let’s talk about what our visions are for the future of Portland, and set our design standards for the community. We here at PDXplore are working on partnering with other like minded groups to do just that. Please reach out if you would like to join that effort.

Wut?